It is likely that Tiger Woods, a mixed-race kid with a middle-class background who grew up on a municipal course in the sprawl of Los Angeles, had his finest day on the overcast Sunday in Augusta when he humiliated the world’s best golfers to win The Masters by a preposterous 12 shots.

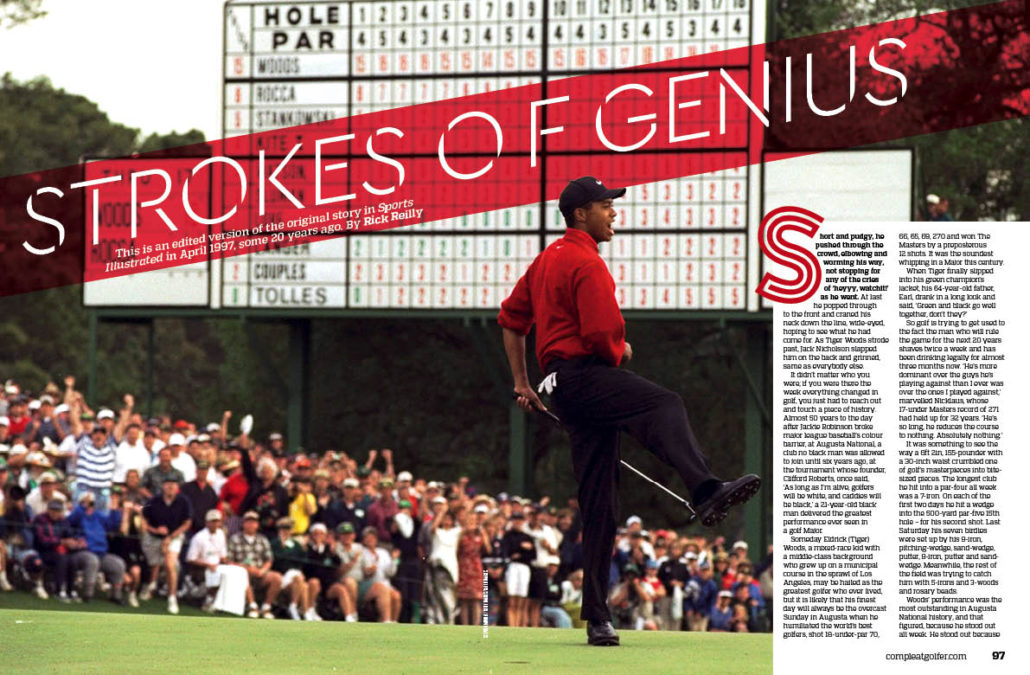

Short and pudgy, he pushed through the crowd, elbowing and worming his way, not stopping for any of the cries of ‘heyyy, watchit!’ as he went. At last, he popped through to the front and craned his neck down the line, wide-eyed, hoping to see what he had come for. As Tiger Woods strode past, Jack Nicholson slapped him on the back and grinned, same as everybody else.

It didn’t matter who you were; if you were there the week everything changed in golf, you just had to reach out and touch a piece of history. Almost 50 years to the day after Jackie Robinson broke major league baseball’s colour barrier, at Augusta National, a club no black man was allowed to join until six years ago, at the tournament whose founder, Clifford Roberts, once said, ‘As long as I’m alive, golfers will be white, and caddies will be black,’ a 21-year-old black man delivered the greatest performance ever seen in

a golf Major.

Someday Eldrick (Tiger) Woods, a mixed-race kid with a middle-class background who grew up on a municipal course in the sprawl of Los Angeles, may be hailed as the greatest golfer who ever lived, but it is likely that his finest day will always be the overcast Sunday in Augusta when he humiliated the world’s best golfers, shot 18-under-par 70, 66, 65, 69, 270 and won The Masters by a preposterous 12 shots. It was the soundest whipping in a Major this century.

When Tiger finally slipped into his green champion’s jacket, his 64-year-old father, Earl, drank in a long look and said, ‘Green and black go well together, don’t they?’

So golf is trying to get used to the fact the man who will rule the game for the next 20 years shaves twice a week and has been drinking legally for almost three months now. ‘He’s more dominant over the guys he’s playing against than I ever was over the ones I played against,’ marvelled Nicklaus, whose 17-under Masters record of 271 had held up for 32 years. ‘He’s so long, he reduces the course to nothing. Absolutely nothing.’

It was something to see the way a 6ft 2in, 155-pounder with a 30-inch waist crumbled one of golf’s masterpieces into bite-sized pieces. The longest club he hit into a par-four all week was a 7-iron. On each of the first two days, he hit a wedge into the 500-yard par-five 15th hole – for his second shot. Last Saturday his seven birdies were set up by his 9-iron, pitching wedge, sand wedge, putter, 9-iron, putter and sand wedge. Meanwhile, the rest of the field was trying to catch him with 5-irons and 3-woods and rosary beads.

Woods’ performance was the most outstanding in Augusta National history, and that figured because he stood out all week. He stood out because of the colour of his skin against the mostly-white crowds. He stood out because of his youth in a field that averaged 38 years. He stood out because of the length of his drives – 323 yards on average, 25 yards longer than the next player on the chart. He stood out for the steeliness in his eyes and for the unshakable purpose in his step. ‘He may be 21,’ said Mike (Fluff) Cowan, his woolly caddie, ‘but he ain’t no 21 inside those ropes.’

It was a week like nobody had ever seen at Augusta National. Never before had scalpers’ prices for a weekly ticket been so high. Some were asking $10 000. Never before had one player attracted such a large following. Folks might have come out with the intention of watching another golfer, but each day the course seemed to tilt towards wherever Woods was playing.

It was the highest-rated golf telecast in history, yet guys all over the country had to tell their wives the reason they couldn’t help plant the rhododendrons was that they needed to find out whether the champion would win by 11 or 12.

Away from the golf course, Woods didn’t look much like a god. He ate burgers and fries, played ping-pong with his buddies, screamed at video games and drove his parents to the far end of their rented house. Michael Jordan called, and Nike czar Phil Knight came by, and the FedExes and telegrams from across the world piled up on the coffee table, but none of it seemed to matter much. What did matter was the Mortal Kombat video game and the fact he was Motaro and his Stanford buddy Jerry Chang was Kintaro, and he had just ripped Kintaro’s mutant head off and now there was green slime spewing out and Tiger could roar in his best creature voice, ‘Mmmmmwaaaaannnnnggh!’

By day Woods went back to changing the world, one mammoth drive at a time. What’s weird is that this was the only Masters in history that began on the back nine on Thursday and ended on Saturday night. For the first nine holes of the tournament the three-time reigning US Amateur champion looked amateurish. He kept flinching with his driver, visiting many of Augusta’s manicured forests, bogeying 1, 4, 8 and 9 and generally being much more about Woods than about Tigers. His 40 was by two shots the worst starting nine ever for a Masters winner.

But something happened to him as he walked to the 10th tee, something that separates him from other humans. He fixed his swing, right there, in his mind. He is nothing if not a quick study. In the six Augusta rounds he played as an amateur, he never broke par, mostly because he flew more greens than Delta with his irons and charged for birdie with his putter, often making bogey instead. This year, though, he realised he had to keep his approach shots below the hole and keep the leash on his putter. Woods figured out how to relax and appreciate the six-inch tap-in. (For the week he had zero three-putts.)

And now, at the turn on Thursday, he realised he was bringing the club almost parallel to the ground on his backswing – ‘way too long for me’ – so he shortened his swing right then and there.

He immediately grooved a 2-iron down the 10th fairway and birdied from 18 feet. Then he birdied the par-three 12th with a deft chip-in from behind the green and the 13th with two putts. He eagled the 15th with a wedge to four feet. When he finished birdie-par, he had himself a back-nine 30 for a two-under 70. Woods was only three shots behind the first-day leader, John Huston.

By Friday night you could feel the sea change coming. Woods’ 66 was the finest round of the day, and his lead was three over Colin Montgomerie. Saturday was nearly mystical. As the rest of the field slumped, Woods kept ringing up birdies. He tripled his lead from three to nine with a bogey-less 65.

That night there was this loopiness, this giddy sense, even among the players, of needing to laugh in the face of something you never thought you’d see. A 21-year-old in his first Major as a pro was about to obliterate every record, and it was almost too big a thought to be thunk.

After playing with Woods on Saturday, Montgomerie staggered in looking like a man who had seen a UFO.

He plopped his weary meatiness into the interview chair and announced, blankly, ‘There is no chance. We’re all human beings here. There’s no chance humanly possible.’

Only 47-year-old Tom Kite, who would finish second in the same sense that Germany finished second in World War II, refused to give up. He was a schnauzer with his teeth locked on the tailpipe of a Greyhound bus as it was pulling into beltway traffic. How can you be so optimistic when Woods is leading by nine shots?

‘Well,’ said Kite, ‘we’ve got it down to single digits, don’t we?’

The last round was basically a coronation parade with occasional stops to hit a dimpled object. There seemed to be some kind of combat for mortals going on behind Woods for second place, but nothing you needed to notice. Nobody came within a light year. Constantino Rocca and Tom Watson each trimmed the lead to eight, but mentioning it at all is like pointing out that the food on the Hindenburg was pretty good.

Woods went out on the front nine in even par, then birdied the 11th, the 13th and the 14th and parred the 16th with a curvaceous two-putt. ‘After that, I knew I could bogey in and win,’ he said. That’s a bit of an understatement, of course. He could’ve used nothing but his putter, his umbrella and a rolled-up Mad magazine and won.

He wanted the record, though, and for that there was one last challenge – the 18th. On his tee shot a photographer clicked twice on the backswing, and Woods lurched, hooking his drive way left. On this hole, though, the only trouble comes if you’re short or right, and Woods has not been short since grade school. He had a wedge shot to the green – if only he could get his wedge. Fluff was lost. ‘Fluff!’ Woods hollered, jumping as if on a pogo stick to see over the gallery.

Fluff finally found him as the crowd chanted, ‘Fluff! Fluff!’

It was not exactly tense.

Still, Woods needed a five-footer for par, and when he sank it, he threw his trademark uppercut. He was now the youngest man by two years to win The Masters and the first black man to win any Major.

He turned and hugged Fluff, and as the two men walked off the green, arms draped over each other’s shoulders in joy, you couldn’t help but notice that Chairman Roberts’ Rule of Golf Order had been turned happily upside down – the golfer was black and the caddie was white.

So golf is all new now. If you are the tournament director of a PGA Tour event, you better do whatever’s necessary to get Tiger Woods, because your Wendy’s-Shearson Lehman Pensacola Classic is the junior varsity game without him.

The Senior Tour seems sort of silly next to this.

At the very end Woods made it into the elegant Augusta National clubhouse dining room for the traditional winner’s dinner. As he entered, the members and their spouses stood and applauded politely, as they have for each champion, applauded as he made his way to his seat at the head table under a somber oil painting of President Eisenhower.

But clear in the back, near a service entrance, the black cooks and waiters and busboys ripped off their oven mitts and plastic gloves, put their dishes and trays down for a while, hung their napkins over their arms and clapped the loudest and the hardest and the longest for the kind of winner they never dreamed would come through those doors.

This is an edited version of the original story in Sports Illustrated in April 1997, some 20 years ago by Rick Reilly.

– This article first appeared in the April issue of Compleat Golfer, now on sale

Photos: Getty Images