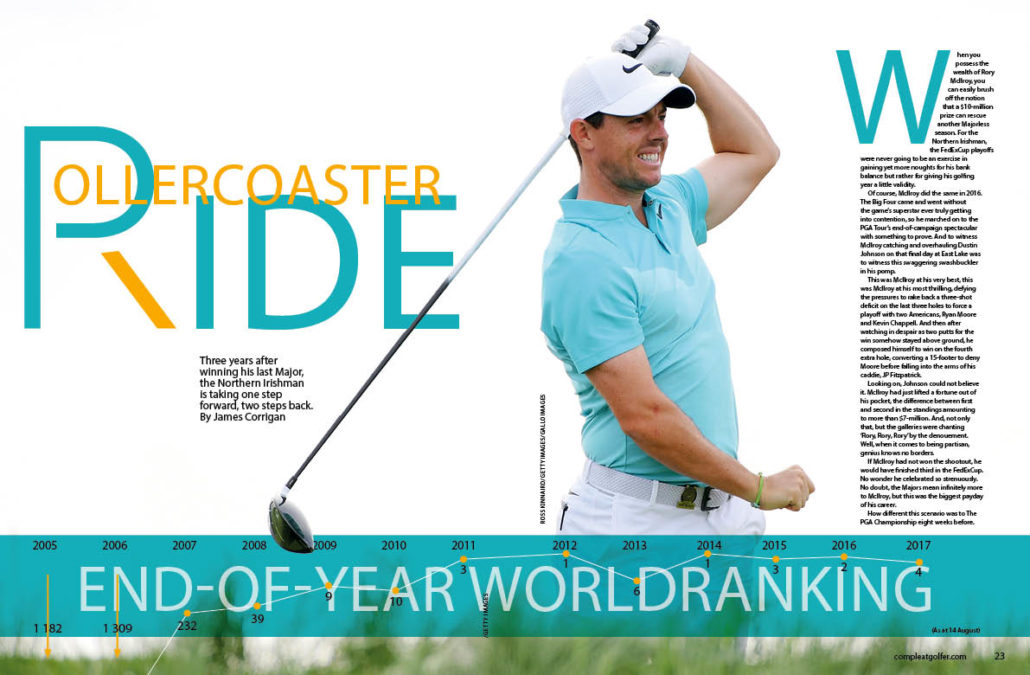

Three years after winning his last Major, Rory McIlroy is taking one step forward, two steps back, writes JAMES CORRIGAN in Compleat Golfer.

When you possess the wealth of Rory McIlroy, you can easily brush off the notion that a $10-million prize can rescue another Majorless season.

For the Northern Irishman, the FedExCup playoffs were never going to be an exercise in gaining yet more noughts for his bank balance, but rather for giving his golfing year a little validity.

Of course, McIlroy did the same in 2016. The Big Four came and went without the game’s superstar ever truly getting into contention, so he marched on to the PGA Tour’s end-of-campaign spectacular with something to prove. And to witness McIlroy catching and overhauling Dustin Johnson on that final day at East Lake was to witness this swaggering swashbuckler in all his pomp.

This was McIlroy at his very best, this was McIlroy at his most thrilling, defying the pressures to rake back a three-shot deficit on the last three holes to force a playoff with two Americans, Ryan Moore and Kevin Chappell. And then after watching in despair as two putts for the win somehow stayed above ground, he composed himself to win on the fourth extra hole, converting a 15-footer to deny Moore, before falling into the arms of his caddie, JP Fitzpatrick.

Looking on, Johnson could not believe it. McIlroy had just lifted a fortune out of his pocket, the difference between first and second in the standings amounting to more than $7-million. And not only that, but the galleries were chanting ‘Rory, Rory, Rory’ at the denouement.

Well, when it comes to being partisan, genius knows no borders.

If McIlroy had not won the shootout, he would have finished third in the FedExCup. No wonder he celebrated so strenuously.

No doubt the Majors mean infinitely more to McIlroy, but this was the biggest payday of his career.

How different this scenario was to the PGA Championship eight weeks before. When McIlroy missed the cut at Baltusrol, he was despondent, referring to his performance on the greens as ‘pathetic’. He sought out Phil Kenyon, the Lancastrian putting coach who works with the likes of Henrik Stenson and Justin Rose.

‘I think you need weeks like that. I’ve always benefited from things like that in my career,’ McIlroy said. ‘It was blatantly obvious what I needed to do in terms of fixing my putting. I started on a process to do that, and I didn’t think results were going to come as quickly as they did. The great thing about this FedExCup is you have something to play for after the Major season. I really wanted to at least give myself a chance in the playoffs.’

And after another indifferent year, starting with a rib injury that worsened after the SA Open, McIlroy had viewed the FedExCup as a chance to raise his hand again, like he had last year. The winning cheques are all well and good, but it’s the actual winning that counts for more.

But McIlroy cut a dejected figure after a final-round 68 left him in a tie for 22nd at the PGA Championship.

‘I don’t know what I’m going to do,’ he said. ‘You might not see me until next year. You might see me in a couple of weeks’ time. It really depends.’

McIlroy complained of spasms in his left rhomboid (upper back) and also said the inside of his left arm was numb. ‘I must have a chat with [fitness coach] Steve McGregor about it and see what we need to do. But the more I play, it’s just not allowing it time to heal 100%.’

After sustaining the rib injury at the SA Open in January, his 2017 has been painful in more ways than one. ‘If I’m capable of playing, I feel like, ‘‘Why shouldn’t you?’’ But then, at the same time, if you are not capable of playing at your best, why should you play? It’s a Catch-22.’

There are those who look at the 28-year-old and see a representative of his age, a ridiculous talent dulled by the ridiculous amounts of greenback piling up in front of him. Steve Elkington, the former Major winner, gave this viewpoint stark expression in June, in the hours after McIlroy missed the cut at Erin Hills.

McIlroy was on board of a private jet flying back to his Florida home when he came under social media onslaught from the Australian. Having watched McIlroy fail to make the US Open weekend for the second year in succession, Elkington, who won the 1995 PGA Championship, tweeted: ‘Rory is so bored playing golf … without Tiger [Woods] the threshold is 4 majors with 100 mill in bank.’

McIlroy had signed a deal with equipment maker TaylorMade the previous month, estimated to be worth $100-million over 10 years, and which hauled his annual off-course earnings to approximately $25-million. McIlroy hit back on Twitter as soon as he landed.

‘More like 200 mill … not bad for a “bored” 28 year old … plenty more where that came from,’ McIlroy posted alongside a screenshot of his Wikipedia entry which listed his achievements in the game. And so it went back and forth, with Elkington saying Jack Nicklaus ‘never mentioned his total cash’. ‘You’re the 200 mill guy,’ he told McIlroy.

In truth, McIlroy would have been far wiser not to become embroiled in spats such as this. Indeed, he knew he should not have reacted and deleted his reply ‘about five times’. But eventually, in his fury, he pressed the send button.

Cue the backlash. While many ‘liked’ his retort, there were also those who thought the ‘200 million’ part flippant, and at worst, boastful. McIlroy obviously regretted it, and no wonder. He is the last person to make a show of his wealth. He asked his wife, Erica, to change his Twitter password and never to tell him what it was. He was logging off for good.

Yet beneath all this social media knockaboutery was a more serious point which pertains to McIlroy’s profession itself. He allowed Elkington under his skin, and although McIlroy claimed it was ‘because he is a former Major winner and someone who should realise how hard golf is at times’, it still proved that, in sport, there are few things as brittle as a golfer’s psyche.

Elkington is a renowned loudmouth who is nowhere near McIlroy’s level as a golfer or, most definitely, as a human being. He should not be able to prey on any insecurity when it comes to McIlroy.

That he was able, is because golf is this most maddening of sports which ensures that the competitor’s mind is beset by self-doubt. Even when that competitor seemingly has everything in the world. In fact, especially when that competitor seemingly has everything in the world. Everything but the season he craves.

To think 2017 began with those joyous scenes in January when huge crowds descended on Glendower Country Club near Johannesburg to see McIlroy beaten by Englishman Graeme Storm in sudden death. McIlroy enjoyed the experience so much he pledged to return, but in terms of his physical well-being he was hurting.

By the summer, the putting had become a problem again and it was one that McIlroy tried to fix himself. ‘With every other part of my game, I have ownership of it. The putting has never felt that way,’ he said.

Kenyon should not have worried; McIlroy retained his services. It was just that he felt too robotic. Perhaps he had listened to Paul McGinley, his friend and former Ryder Cup captain, who had this to say after watching him crash out at the Irish Open.

‘Initially Rory had a lot of success with Phil, but my worry would be he has lost that creativeness, that touch, that feel – that ability to be an artist. That’s when Rory is at his best. It’s not when he has his mind full of structure.’

McIlroy seemed to agree. ‘With Phil, I’ve made some really good strides in terms of what I’m doing technically,’ he said. ‘After the 2016 PGA, I definitely needed work on my stroke. But I’ve become bogged down in technical thoughts. My mechanics are good enough to start the ball on line and now it’s all about getting myself in the right frame of mind.

‘Look at a six-year-old. Give them a putter and a ball and tell them to hole it. There’s no thought. They somehow are just able to do it. It’s about getting back to that mentality and that feel and getting out of my own way.’

McIlroy was blocking McIlroy’s path. He admitted as much. He knew he had to free up and let it happen. But he was also aware that time was not his friend. That is why he elected to dismiss Fitzgerald, the bagman he had been with for nine years and with whom he had won four Majors.

The split came in the wake of him finishing fourth at The Open Championship, and few people saw it coming. The reasons McIlroy gave shone a spotlight on the state of his competitive mind. ‘Sometimes to preserve a personal relationship, you have to sacrifice a professional one,’ he said. ‘I was getting very hard on him on the course and I don’t want to treat somebody, anybody, like that. I felt like it was the right thing to do, and I don’t think there was any good time to do it.

‘It was a tough decision to make, but I’m trying to take ownership of my game a bit more and take more responsibility.’

Ah, the ‘R’ word again. In the year that McIlroy got married, he has tried to become his own man and his own golfer. But the fates and his game have colluded against him. As he has struggled with his putting and his wedge play, Jordan Spieth, four years his junior, has won an Open to get within one Major of him. Nobody would have predicted that when McIlroy won back-to-back Majors in 2014.

‘It’s amazing, it wasn’t that long since we were sat here thinking “Rory’s the new Tiger, he’s our new superstar” and it only seemed a question of how far into double figures he would go with Majors – it was all about him,’ McGinley told me.

Now the narrative is if and when can McIlroy get back on track. All he can do is keep the faith. ‘It’s hard to stand in front of a camera every single time and say to you guys, it’s close; because I sound a bit like a broken record after a few weeks,’ McIlroy said. ‘But really, it’s not far away. I’m positive about it. I’m excited about my game. I feel like I’m doing a lot of good things. And again, it’s just putting it all together. Putting it all together, not just for one day but for four days; and not just for four days, to do it week in and week out.’

The FedExCup was supposed to afford him that opportunity again. ‘I’m capable of playing well enough to give myself a chance in it [despite the spasms],’ he said. ‘At the same time, April is a long way away. The Masters is the next big thing on my radar.’

– This article first appeared in the September issue of Compleat Golfer