Today, every sixth golf course in South Africa is situated on a residential golfing estate. This is quite remarkable, considering that the first local golf estate was established only 32 years ago.

There are two types of residential golf estates – primary and secondary. A third of golf estates can be regarded as primary residential, with the balance consisting mostly of secondary residential (holiday homes). The former tend to be more compact and condensed, whilst the latter often provide hotel- and/or rental pool accommodation for visitors.

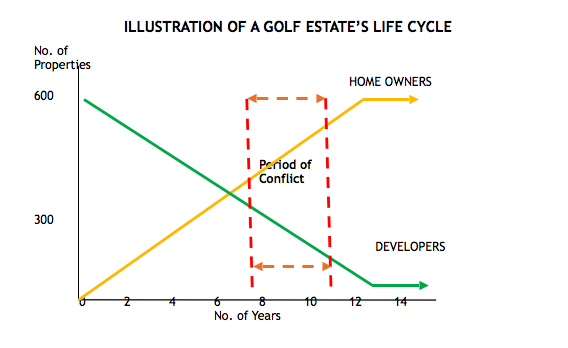

One common denominator prevalent in residential golf estates is its life cycle, with 2 major stakeholders at play. They are the developer (which may change hands at some point in time) and property owners. As a residential estate develops and matures, home owners take on more responsibility and of the costs associated with running such an estate. At some point in time, a tipping point is reached where the collective investment value and hence potential influence of home owners supersedes that of the developers.

This implies that with time, the developer’s influence should diminish as sellable property gets less and private home ownership increases. It often leads to conflict between the developer and the body representing property owners, generally known as the Home Owners Association (HOA). The conflict is exacerbated in instances where the HOA Board consists of developer and property owners’ representatives, with the developer retaining majority representation even when it has nearly sold out property.

Some developers are loathe to relinquish control, as HOA’s may make decisions that developers’ feel will either change their vision for the estate, or affect them financially.

Often a major area of conflict is cost related – it can be of a capital nature or narrowed down to the operational management of the golf course and associated facilities, such as clubhouse and other sports amenities, which is owned and operated by the developer. It is seldom that such operations are sustainable without the contribution of home owners by way of a social- and golf membership subscriptions and/or levies. Developers sometimes restrict the subscription / levy contribution to home owners who want to be members of the golf club. Only 30% of residential owners typically tend to play golf and are likely to subscribe to membership, which means that 70% of owners do not contribute to the upkeep of a golf course and related facilities and this non-contribution puts severe financial strain on operations. No developer will carry operational losses indefinitely and there are a number of ways to deal with it – recover the shortfall from property owners (by way of an additional levy), reduce operating costs (which directly influences service delivery and golf course conditioning), or selling the operations to a third party (whose interests may be different to home owners).

During the life cycle of a golf estate, capital replacement has to take place at various points in time. As a rule of thumb, the majority of golf course machinery requires replacement every 5 years. An irrigation system, including its pumps, requires routine maintenance. MWG has often seen this aspect being neglected, which culminates in either major repairs or replacement down the line. On the estate itself, services such as roads, sewerage, storm water drainage and security also require maintenance and certain upgrading from time to time.

It is important to note at what point in an estate’s life cycle capital replacement or upgrades are required. If proper infrastructure installation and good maintenance are in place, the necessity for replacements or upgrades (except for golf course machinery) should only be required when an estate has reached maturity. At this point, the HOA should be in control and have had enough time to plan and provide for adequate cash reserves to perform such change. A conflict situation may arise when there are changes required early in the life cycle, when the developer still has property to sell while the home owners now have a significant presence. The developer may argue that home owners need to make a financial contribution since they enjoy the benefits of estate living, while home owners may contest that while the developer has property to sell and calling the shots, it is his/her responsibility.

It can lead to a standoff where no party contributes towards the replacement or upkeep of assets, with disastrous consequences. This has often been the case and the relationship between developer and a HOA becomes severely strained to a point that leads to a lack of material decisions being made that could be beneficial to the estate .

It is regrettable to see how few residential golf estates have avoided certain pitfalls – there are well publicised case studies to learn from.

MWG has been exposed to many of these challenges and would advise developers and HOA’s to engage with each other, even if it means facilitating through an independent non-legal third party to avoid conflict that inevitably becomes costly.

By: Francois du Plessis, MWG Business Strategist