Politics and sport. Like it or not they co-exist, one influenced by the other.

It has forever been thus. Back in the late 1980s, anti-apartheid campaigner Sam Ramsamy sat me down in his London apartment and explained why sport was being targeted as part of the international community’s fight against the National Party’s segregation policies.

‘No normal sport in an abnormal society,’ he said, aligning with the non-white Sacos mantra. In 1988, South Africa had made the decision that if it couldn’t go to the world sports arena, it would bring the world’s sport to South Africa.

‘Rebel tours’ were organised, with big money paid to those sportsmen who would defy the international outcry and play in front of mainly white crowds in SA stadiums.

In boxing, Gerrie Coetzee challenged for the world heavyweight title in 1979 at Loftus in Pretoria, while golf’s Million Dollar Challenge was launched in 1981. In cricket, an English XI arrived in the 1981-82 season. Sri Lanka toured a year later, followed by West Indies tours the next two seasons. Australia arrived in 1985-86 and the following year too, while New Zealand’s rugby Cavaliers played the Springboks in a four-Test series in 1986.

What we, as South Africans wanting to separate politics from sport, didn’t quite grasp is that there were consequences to these ‘rebel’ actions. Sure, as South Africans we celebrated the engagement and we partied through the victories against the ‘rebels’. However, the outside world saw things differently.

Those players taking part in the ‘rebel’ tours were sanctioned and many never played internationally again. The Sri Lankan ‘rebels’ even received a 25-year ban from playing cricket.

Then, 1991 came and so did unity in South African sport. The cricketers went to India and met Mother Teresa, while South Africa returned to the Olympics after a 32-year absence and competed in Barcelona. Ramsamy himself was involved in a midnight argument with journalists on the flight over as he defended the squad’s selection, with many arguing that better athletes had been left behind to accommodate non-white representation.

Politics and sport, sport and politics.

Nothing has changed. Russian athletes are now being punished for Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine. You might question what the men’s world No 2 tennis player Daniil Medvedev did to be banned from tournaments. The answer is that he’s a sporting casualty of war. Politics and sport.

So, all those golfers who will compete in the Saudi-backed LIV Golf series must expect what’s coming to them. Even if it’s ‘only’ eight events, it is promoting sport in an abnormal society; the Saudi flag-waver in chief, Greg Norman, saying on behalf of the kingdom that “We’ve all made mistakes” and “The good the country is doing in changing its culture”.

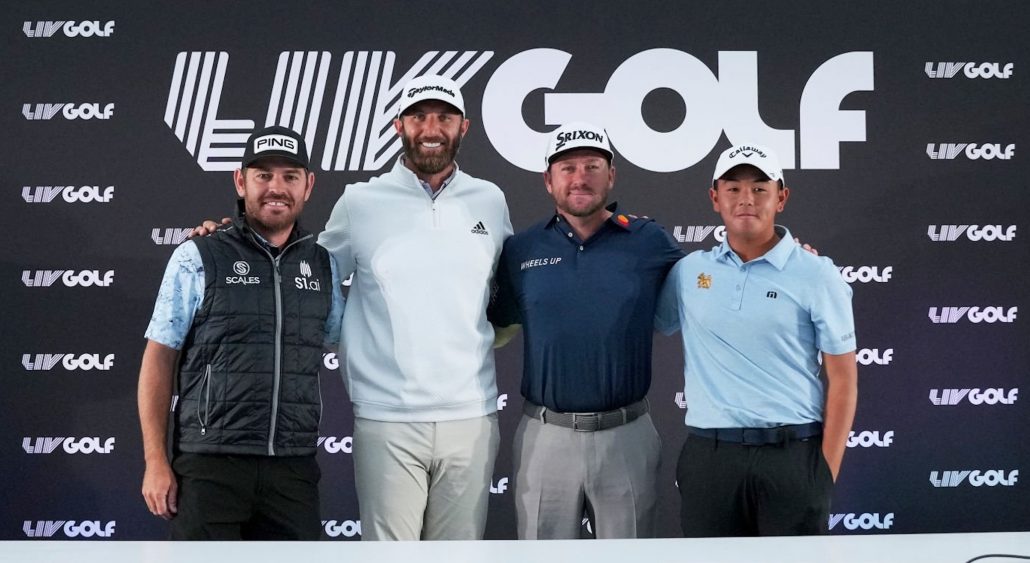

WATCH: Louis and co on joining LIV Golf

There’s plenty of ‘whataboutery’ going on in defending those golfers taking the Saudi cash. But one can’t compare playing other golf tournaments in Saudi Arabia, or a Formula One race. In this case, the golf series is being backed by the government, which has one of the worst human rights records on earth.

But, sure, just like there was a market for ‘rebel’ sports tours to South Africa in the 1980s, there’s a market for a breakaway golf series. Those golfers who commit to it will be making millions of dollars overnight. They won’t have to swing a club on any Tour again to set themselves and their families up for life.

But, don’t defend it as ‘growing the game’. Just admit it for what it is: a get rich(er) quick scheme. It’s about the money, that’s all. It’s their decision. Just don’t expect to be welcomed back to the PGA Tour and DP World Tour with open arms. It’s nothing personal, but there have to be lines drawn in the desert sand. You can’t just hop from one Tour to another, rake up the money and return as if nothing has changed.

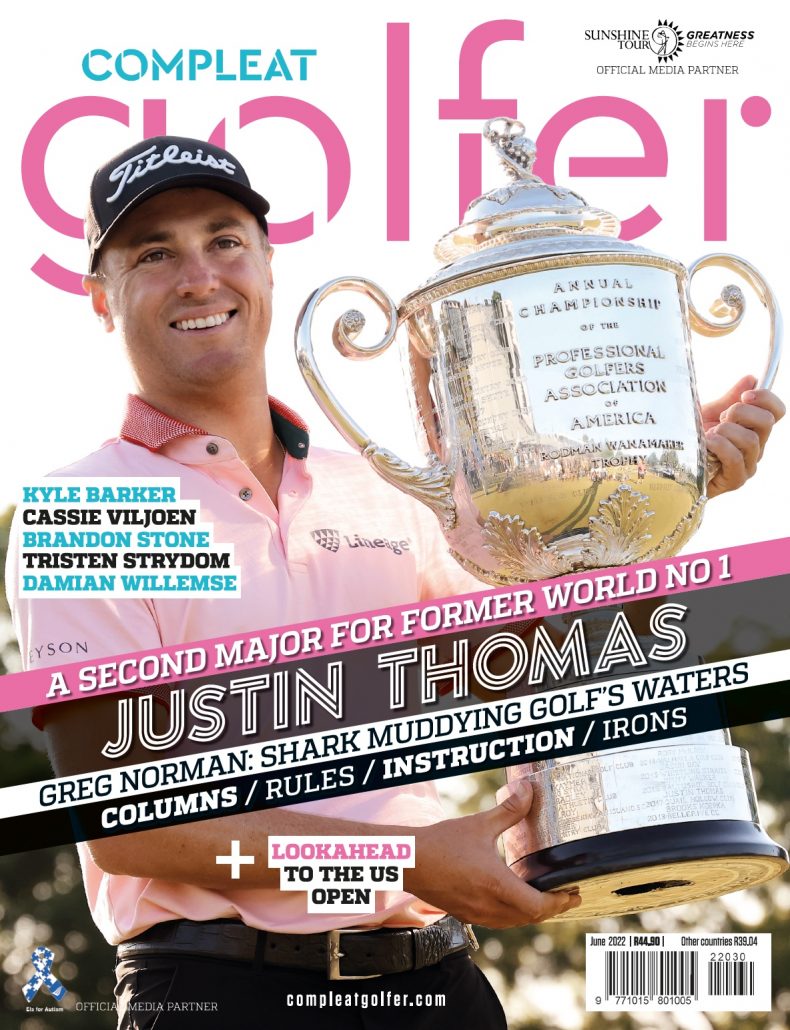

– This column first appeared in the June 2022 issue of Compleat Golfer magazine. Subscribe here!